The A-word.

It's the bane of cinephiles, everywhere.

That book you love; the comic you remember; the show you used to watch; the game you lost an entire summer playing? Oh, someone's adapted it and it's getting made into a movie! Whether a cause for pre-emptive celebration or foreboding caution, it leads to only one thing: expectation. And expectation is the death of the 'clean' movie-viewing experience; no matter how closely the film sticks to its source material, or how much it tries to distance itself, it will be faced with the hurdle of comparison.

And while the movie industry loves the pre-built marketing buzz of 'now a major motion picture!', they loathe the comparative references which will be made from the first review onwards. Because many punters will expect to get exactly the same reaction from a completely different medium, to a story they already know. And therein lies the problem.

In this monthly series, we'll look back at some of the most respected and best-loved properties which have made the perilous journey to the big screen; often with some controversy, and almost always with far too much hype. This isn't so much a review of the films themselves, more an appraisal of their suitability as an adaptation.

Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?

Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?

Philip K. Dick (1968)

I was lucky in that I'd (inadvertently) picked an edition of Androids featuring an introduction by Paul McAuley. Printed in 2011, the three-page opener tells the reader eloquently, yet bluntly, to un-remember the film which will no doubt be first and foremost in their mind. It should be obvious that the 1968 book isn't a novelisation of the 1982 movie, but it's a point which bears stating at the outset.

In Dick's Los Angeles of 1992, a radioactive dust hangs in the air and killed most of Earth's wildlife in the early days of 'World War Terminus'. Any remaining animals are extremely rare, and owning/caring for one has become both a social and moral duty, as well as a status-symbol. For those who cannot afford a real animal, electronic replicants are available. But the planet is essentially dying, with most of the surviving inhabitants having moved out to colonies on Mars and beyond. The remaining humans on Earth huddle under the spiritual umbrella of a secular-religion Mercerism, based around shared empathy, and use a domestic appliance known as a Mood Organ to generate emotion on demand, counteracting (or even causing) whatever anxieties are on their minds. Aspiration, reassurance, faith and narcotics; times may change, but human behaviour does not.

As an inducement to relocate, the authorities offer migrants their own personal android-assistant, off-world. Manufactured by The Rosen Association, these ever-improving machines grow more interwoven in their extra-planetary societies, but are still viewed as equipment, despite having intelligence and self-awareness. What they lack is spontaneous empathy, a trait which their manufacturers have been unable to simulate via programming. Any androids who manage to escape their servitude usually make their way to Earth, where they realise a less-dense population offers more places to hide.

Taking place over roughly 24 hours, the story follows state-licensed bounty hunter Rick Deckard, in the middle of squabbling with his wife as he's called in by the LAPD to retire six escaped Nexus 6-model androids after they hospitalise his colleague, Dave Holden. Among them is the group's leader Roy Baty, his android wife, Irmgard, and Pris, who hole up in the ramshackle apartment of simple-minded delivery driver, J.R. Isidore (the character who becomes J.F. Sebastian for the film). But what the machines apparently lack in emotional judgement and experience, they more than make up for in raw strength and intelligence. In order to complete his assignment, Deckard travels to The Rosen Association headquarters in Seattle, where the enigmatic Rachael is tasked to assist him, being a legalised Nexus-6 herself.

+ + + + +

Far more introspective than its cinematic offspring, this is a book about empathy, identity and consciousness. Those themes exist in the adaptation as well, of course, but here they make up most of the inner dialogue. And while Rick is still handed the assignment in much the same circumstances, the interaction with his quarry is more in-depth than just point/shoot*1. It's this engagement which leads to the mercenary questioning his own empathy, and frequently. The notorious question of 'is Deckard a replicant?' is dealt with directly here, and by Deckard himself (although I won't tell you which way that turns out).

A fairly slim volume at 193pages (my edition, at least), Philip K. Dick doesn't waste too much time describing the scenery, keeping the story moving forward with each compact chapter. The spectre of implanted-memories raises its head again, arguably with better impact than in his story which was about implanted memories. Dick also focuses far more on the above-mentioned conversations between Deckard and the rogue-androids, than when the hired killer finally despatches them. The retirements are treated as punctuation at the end of a life-sentence, rather than a reflective denouement. Not to get too spoiler-ific, but you remember in Blade Runner when the final showdown with Roy progresses from a tense lengthy shootout to a rooftop chase, then rain-soaked iconic soliloquy? Here's how it plays out on paper...

"I'm sorry, Mrs Baty," Rick said, and shot her. Roy Baty, in the other room, let out a cry of anguish.

"Okay, you loved her," Rick said, "And I loved Rachael. And the special loved the other Rachael." He shot Roy Baty; the big man's corpse lashed about, toppled like an over-stacked collection of separate, brittle entities; it smashed into the kitchen table and carried dishes and flatware down with it. Reflex circuits in the corpse made it twitch and flutter, but it had died.

Rick ignored it, not seeing it and not seeing that of Irmgard Baty by the front door. I got the last one, Rick realised. Six today; almost a record. And now it's over and I can go home.

No Tears In Rain, here. But the book isn't Roy's story, it's Rick's. That's not to say the artificial lifeforms don't each become characters in themselves, but we see everything that happens through the eyes of Deckard, or of Isidore, the radiation-addled loner who's high on empathy but low on social-skills. The humanity the androids develop (for better or worse) isn't explored too deeply, as it's laid out plainly that these beings aren't physically human. We can't understand what it's like to actually be them any more than we could put ourselves in the mind of a dolphin, or more accurately an alien. Humanity is specific, empathy is universal.

+ + + + +

As well as the upfront issues of self-awareness, there's also an intricate subtext of guilt being played out in the pages. The humans don't trust the independent thought of their android servants as they perceive them as lacking in empathy. But this flaw is a by-product of the humans' manufacturing process; it can't be programmed in, so can only develop with time and interaction, the way it does in other animals. The problem is that androids only live for around four years (explained in the book as being that their cell-generation can't match the demands put upon it by the machine itself), so at best they're only going to attain the emotional understanding of a toddler. Couple that with being treated as hardware and it's no surprise that the androids start wanting a better life for themselves, a recurring theme in science fiction.

So the Rosen Association has progressively created a life-like machine, driven by market demand. The public treats the machine as a disposable object, the disposable object objects. The authorities decide that the machines can't be allowed to exist under their own auspices, ostensibly because their lack of pathos could cause them to kill a human when confronted in a deadly situation. In reality, their judicial reaction of sentencing runaway androids to 'retirement' is born of fear and guilt. The collective society in the story, already in a state of contrition after a devastating war, cannot see that it is responsible for its perceived nemesis at every single turn, not least because the androids have been literally modelled in their image. A generation which prides itself on empathy has such a narrow definition of the word that it can't see the threat it's created, or the irony of restricting the emotion to beings it can control.

Make no mistake, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a story about a bounty hunter going out to kill six escaped slaves because society deems them to be less than human. It is a tale for past, future and indeed present times.

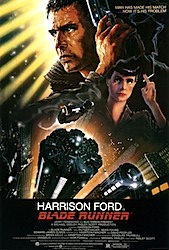

Blade Runner (U.S. Theatrical Cut)

Blade Runner (U.S. Theatrical Cut)

Ridley Scott (1982)

And so, in the hands of screenwriters David Peoples and Hampton Fancher, 1992 becomes 2019 with Los Angeles in a near-permanent state of filth and rain-soaked darkness. Gone is the domesticated discontent of the novel, as Harrison Ford's Rick Deckard lives divorced and alone in a morose ponderousness of bourbon, takeaway noodles and melancholic piano-playing. The protagonist's narration*2 pulls the telling into full film noir and centres it solely around him. He's certainly more of an actual detective this time around. Deckard feels a little older than before, and the story sees him being pulled (with no shortage of intentional irony I'm sure) out of retirement to conduct his mission, although the six escaped replicants of Blade Runner have already killed twenty-three humans on their way to Earth, making Deckard's lethal mandate more narratively justifiable.

The androids are referred to exclusively as replicants now, and script references to genetic engineers indicate that there is indeed little or nothing electronic/mechanical about them, where this was more vague in the book. There are still artificial creatures in the story and the Voigt-Kampff test still centres around hypothetical situations involving cruelty to animals, although there's nothing in the film to indicate how/why biological ones are so hard to come by. World War Terminus doesn't get so much as a sniff.

As Deckard's role remains central, the development of J.R. Isidore / J.R. Sebastian is transferred onto the replicants, which given the film's finale is entirely fitting. In this version, it's Sebastian who becomes more the sketched-in archetype, with his backstory retooled to be more useful to the tweaked plot structure. Along with replicants Pris and Roy being given more of the limelight, it's also notable that the informant Rachael is a far more sympathetic character than her written counterpart. In Dick's novel, Rachael and Pris look identical, being the same model android. And although Sean Young and Daryl Hannah are fantastic here, I'd be intrigued to see the film where either actress plays both roles.

The screenplay runs on a parallel track to the novel, with new characters and situations, but always heading in the same direction and for the same reasons. As with earlier entries in this series, the film expands, reinterprets and amplifies the cinematic aspects of its source material. Ridley Scott does an admirable job of carrying over the psychological and moral themes of the story, but with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, brings a visual poetry to the cityscape that even Philip K. Dick hadn't envisioned.

Ridley Scott's taken something that was very good and made it very great. That's a rare ability, and one that even he hasn't mastered using consistently.

I await 2049*3 with reserved excitement…

It is, very much so.

And far more accessible than I'd be led to understand.

It is, very much so.

But you knew that already.

Both, obviously.

Apparently not.

Level 1: The film's got that Han Solo in it.

And that Princess Leia.

*1 On this subject, the Voigt-Kampff personality-test is very much a part of the novel as it is the film, and with similar mechanics it's not explained why androids can best be discovered via this laborious process, as opposed to heat-readings, EMP-scans, x-ray etc. There's the implication that they're constructed with mostly organic (and nano-electronic) components, but there'd still be some massive physical internal differences, surely? But look at me, wanting everything explained…[ BACK ]

*2 I'd forgotten quite how laconic Ford's voiceover is. At one point it reminded me of My Name Is Earl. "Yup, that brought me to #22 on my list: Shot an android stripper in the back…" [ BACK ]

*3 Anyway, 2019's not far off. Where's my voice-activated Polaroid-printing machine? Actually I joke about it, but it's only really like someone smashed Siri and Instagram together. Which is more 21st Century that I'd like to think about, frankly… [ BACK ]

DISCLAIMERS:

• ^^^ That's dry, British humour, and most likely sarcasm or facetiousness.

• Yen's blog contains harsh language and even harsher notions of propriety. Reader discretion is advised.

• This is a personal blog. The views and opinions expressed here represent my own thoughts (at the time of writing) and not those of the people, institutions or organisations that I may or may not be related with unless stated explicitly.

I'd love to see a film version more accurately adapting 'Do Androids...' It'd be so different from Blade Runner.

ReplyDelete